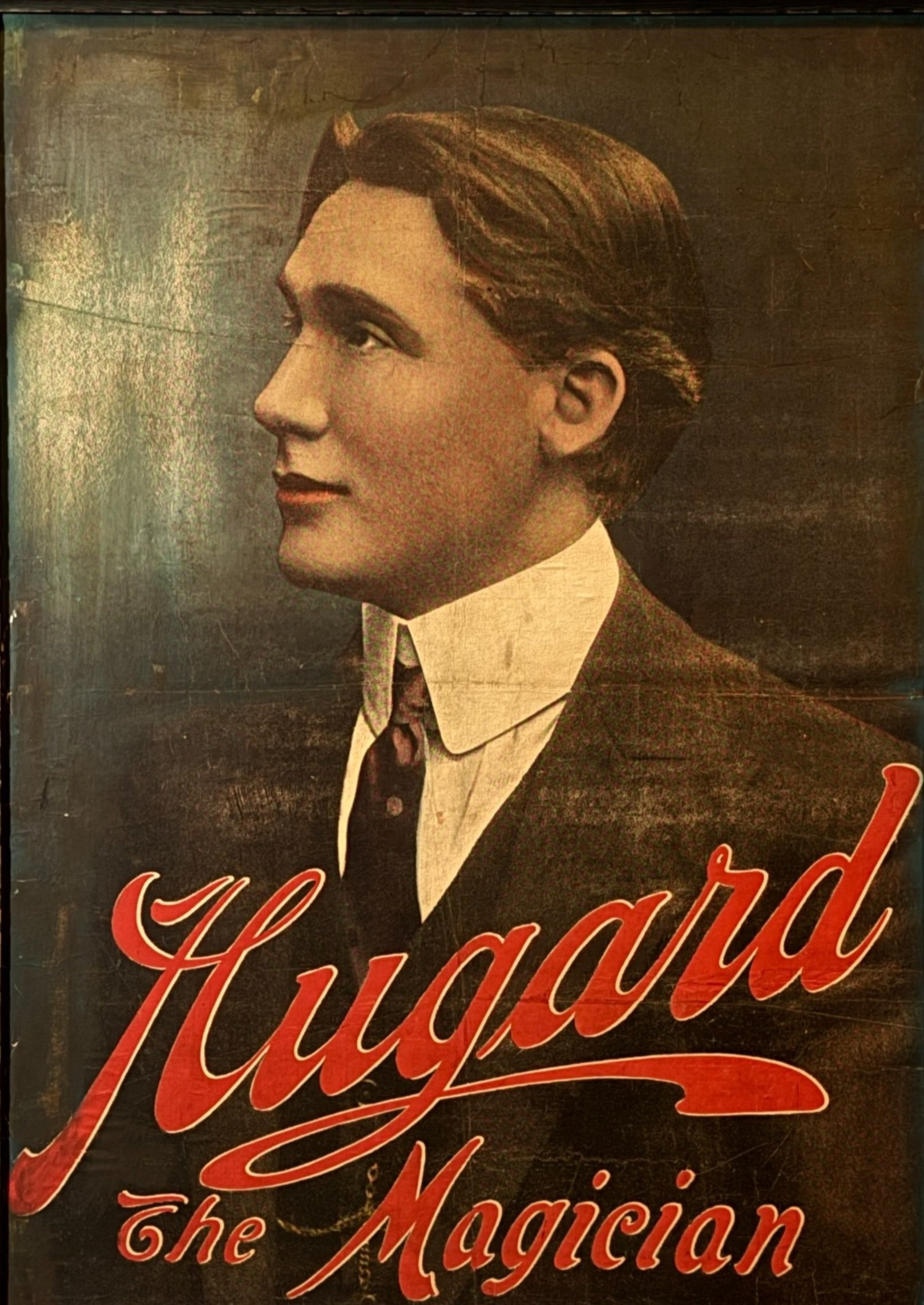

Jean Hugard & His Modern Miracles

By William Pack | Magician, Historian, and Educator, https://libraryprogramming.com/

Hugard the Magician. Melbourne & Sydney: Syd Day the Printer, ca. 1920.Jean Hugard

(John Gerald Rodney Boyce)

B. December 4, 1871 – D. August 14, 1959

Hugard was born John Gerard Rodney Boyce, one of eight children in Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia. After a late start and from a completely non-theatrical background, he rose to become one of the world's great stage magicians, often dubbed the Dean of Magicians and one of the most influential authors on the art of magic.

At age 9, he was inspired by seeing magician Louis Haselmayer’s show. He also studied Jean Eugene Robert-Houdini’s book, “The Secrets of Conjuring and Magic, or How to Become a Wizard.” He eventually began his professional career in 1896. In the course of his life, he performed as Oscar Kellmann, Chin Sun Loo, Ching Ling Foo, and Jean Hugarde.

At age 21, he joined the staff of the Queensland National Bank. In 1898, Hugard left the bank and, with several partners, founded a meat packing company. After a few years, the company failed. It was also during this time that he had an abscess in his ear, which made him partially deaf. Hugard returned to Toowoomba to a series of temporary jobs, including a stint as secretary of the Toowoomba General Hospital. He organized entertainments to raise funds in that capacity, including himself on the bill as an increasingly expert conjurer.

He traveled with five to fifteen assistants and twelve to thirteen tons of baggage for a full evening show. In the first half of the show, he wore evening clothes. He performed card manipulations, small magic, escapes, and his version of the bullet catching trick, which he called "The Great Rifle Feat." He was the first to present it with modern-day guns at the time. Jumping on the fad of non-Asians pretending to be Asian, he performed in Chinese costume and make-up in the second half of the show. He performed the Chinese Rings and several large illusions like the Birth of a Sea Nymph, a baffling production of a beautiful woman from a giant shell.

In 1916, he landed in San Francisco, intending to play across the United States and on to England, Europe, and beyond. He caught on to the Keith, Loew, and Procter vaudeville circuit, playing America for two years. Due to the limitations of vaudeville, his 2 ½ hour full evening show was whittled down to twenty-five minutes.

During the following ten years, from 1919 to 1929, Hugard leased a theatre at Luna Park and was one of the big feature shows at Coney Island, then America's playground. During the winter months, he went on the road with his full evening show. He also appeared in a Broadway Show in 1928 at the Forrest Theater called "The Squealer."

In 1929, in the midst of his plans for a continuation of his world tour, the stock market crashed, the bank in which he had his life's savings closed, and Jean was forced to start over. Not a very cheerful outlook for a man who had almost reached his 60th birthday. Never daunted by adversity, Jean turned his sleight-of-hand talents to teaching and writing to the great benefit of all magicians. Year after year, he published the latest and best sleight-of-hand instruction for the modern magician.

Never daunted by adversity,

Jean turned his sleight-of-hand talents

to teaching and writing

to the great benefit of all magicians.

He wrote more than 50 books on magic. John Northern Hilliard, who was compiling material for the book “Greater Magic,” died, leaving much of the manuscript to be completed. Carl Waring Jones, the book’s publisher, hired Jean Hugard to complete and enlarge the text to over 1,000 pages. The book went on to become a standard textbook of magic, which even modern magicians call "one of the best books ever written about magic." He edited and published “Hugard's Magic Monthly” for seventeen years. In 1951, he was the fourth man to be named the Dean of American Magicians by the Society of American Magicians.

Near the end of his life, Hugard was blind, having lost sight in both eyes following cataract operations. Despite this handicap, he continued to dictate precise magic instructions until a week or so before his death.

He died at the age of 87 and was known far and wide as The Great Hugard. The New York Herald Tribune published a double-column obituary with his photograph – the sort of space usually reserved for statesmen or movie stars.