A brief history of magic posters

By William Pack | Magician, Historian, and Educator, https://libraryprogramming.com/

An Overview

Many of the posters at the Chicago Magic Lounge showcase performers from "The Golden Age of Magic"— a period spanning roughly from the 1880s to the 1930s that saw magicians soar to unprecedented heights of international celebrity. These stars of magic became a staple of Broadway theatre, vaudeville, and music halls.

Those years were also the golden age of posters. Stone lithography, developed around 1798 in Germany, became increasingly popular in the wake of the American Civil War, partly because it was cheap. By the 1880s, the process was widely used in advertising, with magicians and circuses taking the greatest advantage of the large, colorful advertising posters plastering them on every available surface.

Color or Chromolithography is a complex printing process. Artists drew an image on a fine-grained limestone slab with a lithographic grease crayon. An acid wash created an etching where the stone was not protected by the grease. This was washed with water, and an oil-based ink was applied with a roller. The hydrophobic ink fixed to the greased area and was repelled by the damp stone allowing images to be printed on paper. Chromolithography involves multiple layers of printing with different ink colors and, eventually, translucent inks that would blend to create different color tones. Some complex artworks took 20 or more stones to create the full image.

Sizes vary, but the posters generally came in ½ sheet, 1 sheet, 3 sheet, 8 sheet, and 16 sheet sizes. The stones used were usually 1 sheet size, 30" X 40", and weighed over 400 lbs. They would be ground smooth after the printing process until they were too thin to be used.

The Strobridge Lithographing Company of Cincinnati, Ohio, is considered the finest of all the "Golden era" printers. They perfectly captured the fantastical world of magic and the magician's personality. These works fired the public's imagination and filled theaters with ticket buyers. That last bit about ticket buyers is the most important. We may think of these posters as magnificent art, but working magicians are a pragmatic lot. They only cared if the poster was good advertising. Any discussion of poster art should be filtered through the idea of "Did it sell tickets?"

The Houdinis, Harry, Bessie introducing the only and original, [approximately 1895]., Library of CongressBroadsides

Broadsides—by far the most popular ephemeral format used throughout printed history—were single sheets of paper, generally printed on one side only. Often quickly and crudely produced in large numbers and distributed free in town squares, taverns, and churches. Broadsides were intended to have an immediate widespread impact and then to be thrown away.

The early broadside format for magicians generally consisted of a small woodcut or etched picture of the magician and/or his exotic stage paraphernalia. The bulk of the advertisement was printed with florid typography and grandiose language. The copy listed the panoply of magical and entertaining feats in the exhibition. Rarely would there be any occult-type symbols in these posters. If they were used, they were alchemical or astrological. More often, the only symbols used would be masonic. It made sense. A mason was a person of some standing in the community, a respectable man. For the itinerant performer, it provided an instant connection with local men, many of who were prominent members of that community. If the magician had performed for royalty, he might have printed the Royal Seal on the advertisement.

Pre-Golden era

posters

Improvements in the printing process made visual images more important after the Civil War. The posters are ornate, colorful, and idealized versions of the magicians and their shows. The subjects appear younger, taller, more handsome, more regal, and more powerful than they were. The settings are more elaborate, costly, and exotic than the real-life stage dressing.

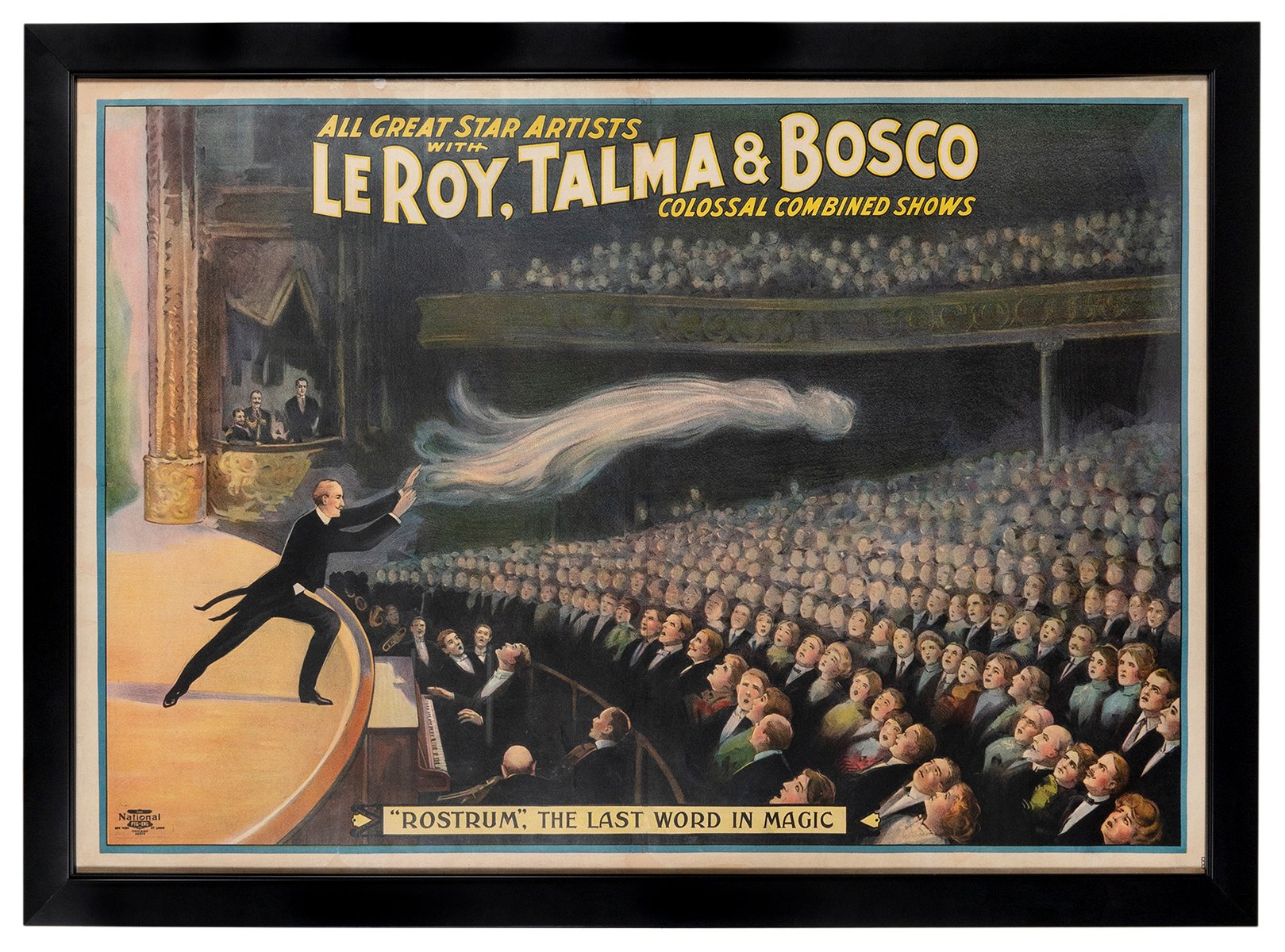

Once again, the posters depicted the magician and his show, the props, tricks, and illusions. Instead of a realistic depiction, more fanciful artwork ruled the day, often omitting essential parts of the illusion. Charles Carter's 1926 poster "Sawing a Woman in Half" does away with the much-needed wooden box. Servais LeRoy's wife was depicted floating and vanishing high above the audience when the actual illusion was performed deep near the back of the stage. The artwork was designed to tell the story of the trick without revealing the trick. The audience could then imagine the wonder they would feel during the performance.

Clockwise from top left: 1. [Magician holding rabbit and conjuring spirit surrounded by demon and owls], c1899., Library of Congress. 2. Carter the Great, 1926. , 3. All Great Star Artists with Leroy, Talma and Bosco, 1907.During this period, any alchemical or astrological symbolism vanished from the posters. With the rise of spiritualism and seances at the time, sometimes ghostly figures and skeletons appeared on posters. Many magicians had séance exposures in their shows or their own recreations of the darkroom tricks.

Clockwise from top left: 1. Heller's Wonders, undated., 2. Last Night of the Wizard! Professor Anderson in Magic and Mystery., circa 1860s., 3. [Magician pulling roses out of top hat surrounded by supernatural beings]., circa 1892., Library of Congress. 4. Théâtre Robert-Houdin, Les Spectres et le Manoir du Diable, circa 1890sGolden Era

Posters

It is all Harry Kellar's fault. An 1886 Chicago Tribune advertisement asked the question, "Kellar. Is He Man or Devil?" Magician Harry Kellar would adorn his posters with devils, imps, and other creatures from the infernal regions. As his popularity rose, many magicians jumped on the bandwagon and copied his iconography.

Kellar Drinks with the Devil, 1899In the middle of the 19th Century, Spiritualism is a shooting star. But there is also a rise in millennial religious movements, doomsday cults, concerns about the rituals and powers of the masons, and huckster preachers, among others. These topics were daily newspaper fodder and in fore of the public's minds.

Kellar saw this as a smart marketing angle. Devils, Imps, secret books of knowledge (grimoires), and a dark universe of symbols positioned the magician as a repository and manipulator of this arcane knowledge. The devils, variously depicted as black, green, and red, became standardized as red around the middle of the 1800s. These familiars of Satan taught magicians the secret knowledge used to defy natural laws. Malevolent forces would be players in his act. Exciting stuff.

Clockwise from top right: 1. Kellar's Startling Wonder, circa 1894, 2. Blackstone The World's Master Magician, 1915, 3. George The Supreme Master of Magic, circa 1926. Of course, the audience knew that devils weren't really helping the magician. But it was a fun fantasy. Think of it like a haunted house. You know it is not real. Yet, it's a thrilling experience, a real-ish but safe experience. Going to a magic show at the turn of the 20th Century had that same feeling: the experience of something forbidden and taboo.

Magic was for adults. Although, there was nothing genuinely objectional in the show. In fact, magicians may have had female assistants on their posters, but unlike the circus, they weren't provocatively clad. Magicians weren't trying to sell sex. Unfortunately, this pushed people to misperceive all magical entertainment as suitable for children. A problem still today.

That is the real lure of this advertising. The audience is drawn into the mystery, marvel, and escape the everyday.

Post-1930s

The death of the large touring show occurred in the late 1930s. The Great Depression and World War II built the coffin, and the movies nailed it shut. Inexpensive movies were the entertainment of choice. Magicians tried to perform in increasingly smaller theaters, the remaining that hadn't been converted into cinemas. Some would perform short sets between movie showings. With the death of the traveling show came the end of the magnificent poster artwork.

Offset printing, also called offset lithography or litho-offset, became a widely used printing technique in commercial printing. The inked image on a printing plate is printed on a rubber cylinder and then transferred (i.e., offset) to paper or other material. This process was more efficient and made it easier to print photographs.

At this time, magicians reached back to a simpler style. Generally, the poster "artwork" consisted of a picture or two of the magician and/or his tricks. The rest was the basic information for the show, Place, Date, Time, and Price. There might be a screamer or so on the poster, such as THRILLS! LAUGHS! UNBELIEVABLE! The poster often had a generic stock background. The small window cards (14x22) were printed on cardboard and set in store windows.

Fetaque Sanders World's Finest Magic Show., Unknown.The Modern Era

These days, with advertising primarily online, there is little need for posters though some are still produced. Magicians are a nostalgic lot. Posters today often copy the fantastical artwork of the Golden Era. Others use modern graphic design, either professional or self-generated in Photoshop. While the variety of styles has never been greater than in any other era, the object is still the same. Convey the "feel" of the show and sell tickets to the show.

original poster design by Kyla Moffatt