MAn of many mysteries

By William Pack | Magician, Historian, and Educator, https://libraryprogramming.com/

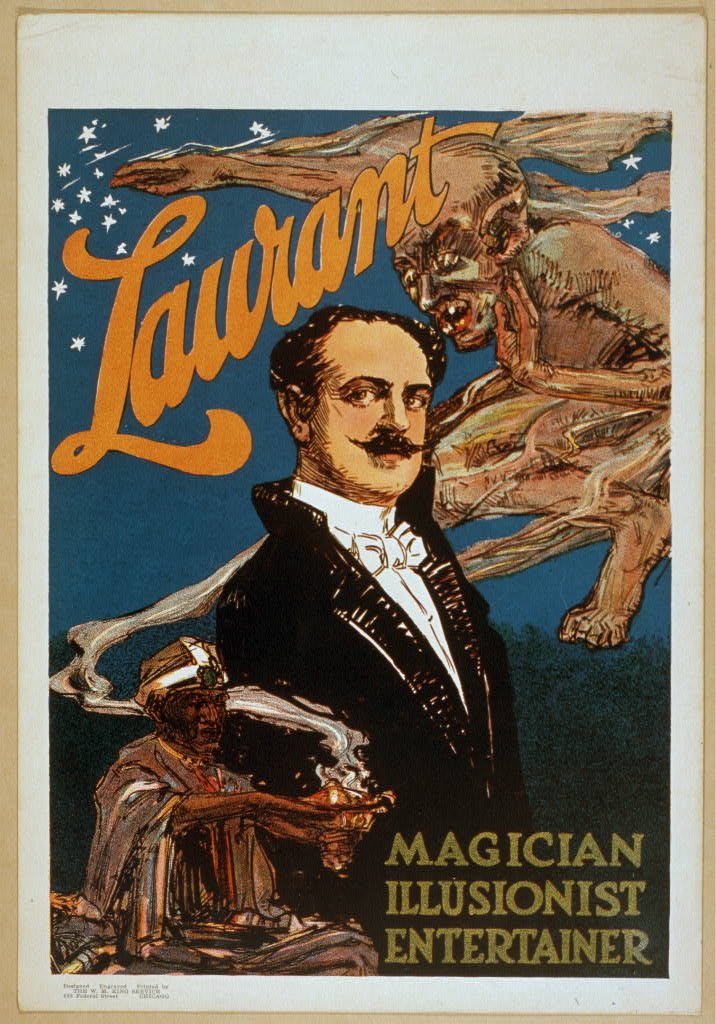

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.printEugene Laurant

(Eugene Lawrence Greenleaf)

B. August 19, 1875 - February 19, 1944

As a boy, Eugene hung around the Denver, Colorado, dime museums, trying to make friends with the magicians performing there. One such performer was a Frenchman named Bernier. Eugene persuaded him to show him some tricks. There may have been an exchange of some money as Bernier was in financial straits. The tricks taught were not the first Eugene had ever learned, but they were of professional quality. He learned rope ties and handcuff escapes, which he used all his life.

Eugene began to believe he could be a magician, and fate helped him along the way. Bernier left Denver, leaving behind a trunk for security for an overdue hotel bill. Shortly after, Eugene received a letter from Bernier proposing that if he paid the bill, he could keep the trunk and props. Soon, a new magician appeared on the Denver scene: Eugene, the Boy Magician.

Eugene still had much to learn. However, one of the great schools for a magician has always been watching professional magicians at close range. Eugene got a job at the Tabor Grand Opera House, working his way from call boy to usher to head usher to ticket taker. He was able to see the greatest talent of the era, performers of all genres. This theater was his university, and it taught him stage deportment, projection of personality across the footlights, and showmanship. He saw Alexander Herrmann’s show twenty-eight times.

In 1898, Eugene joined a vaudeville act and took the professional name “Laurant.” In October, he joined the Magnascope Exhibition Company, one of the first companies to exhibit motion pictures. The film was part of a four-act show. Laurant was billed as “Laurant, the Man of Many Mysteries.”

In 1899, he married Miss Nella Davis, who immediately joined his show as an impersonator of various characters, from “the irrepressible small boy” to “the elderly spinster” and a whistler of bird calls. About this time, Laurant booked his first performances in the Boulder, Colorado Chautauqua. By the last decade of the nineteenth century, the Chautauqua Institution was nationally known as a center for rather earnest but high-minded activities aimed at intellectual and moral self-improvement and civic involvement. Laurant shared the stage with William Jennings Bryan. In later years, he traveled with Bryan on Chautauqua. Bryan lectured in the afternoon, and Laurant’s show filled the evening spot.

Laurant was a superstar on the Lyceum and Chautauqua Redpath circuit. The Redpath Lyceum Bureau was to Chautauqua what Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey were to circus. Laurant became Redpath’s greatest draw.

By 1906, Laurant established himself as a theater performer as well. This was most unusual, if not unique. Few other Lyceum magicians could fill their free time with engagements at theaters in large cities. Laurant was a great performer of both small magic and grand illusions.

His “Witch and Flame” illusion was one of his great inventions. Laurant wore a robe and mask and began by putting his assistant (dressed as a witch) in a vertical casket through which swords were thrust. The witch could be seen through the glass windows on the side of the casket. The witch screamed and Laurant opened the casket, now a fire erupted in the casket. Each time Laurant opened the casket, ten-foot flames shot out. On the final opening, a devil stepped out of the casket. Laurant wrestled the devil back into the fire. Suddenly, a man stood up in the audience and shouted for the magician to put out the fire. A spotlight was thrown on the shouting man, and it was Laurant! The figure onstage was unmasked and shown to be the very witch who had been roasted in the casket. Dramatic illusions like this propelled Laurant to his position among the very best of American magicians.

Dramatic illusions like this propelled

Laurant to his position among the

very best of American magicians.

Laurant continued scoring successfully through the years, playing the best that Lyceum and Chautauqua had to offer and filling the gaps with theatrical engagements. However, all good things come to an end, and Chautauqua died. Most historians cite the rise of car culture, radio, movies, and the depression among the causes.

After 1933, Laurant began working as a forty-miler out of Chicago, literally working a forty-mile ring around the Chicago area. He worked schools, social centers, and private shows into the 1940s. He was active in the local magic community, serving as president of the Chicago Society of American Magicians Assembly, national vice president of the S.A.M., and past vice president of the International Brotherhood of Magicians.

He slowed down but never completely retired. He was at home preparing for a show when he died of a heart attack in 1944. On May 1, his ashes were placed in a crypt in the mausoleum at Rosehill Cemetery, Chicago.