CArter the gReat

By William Pack | Magician, Historian, and Educator, https://libraryprogramming.com/

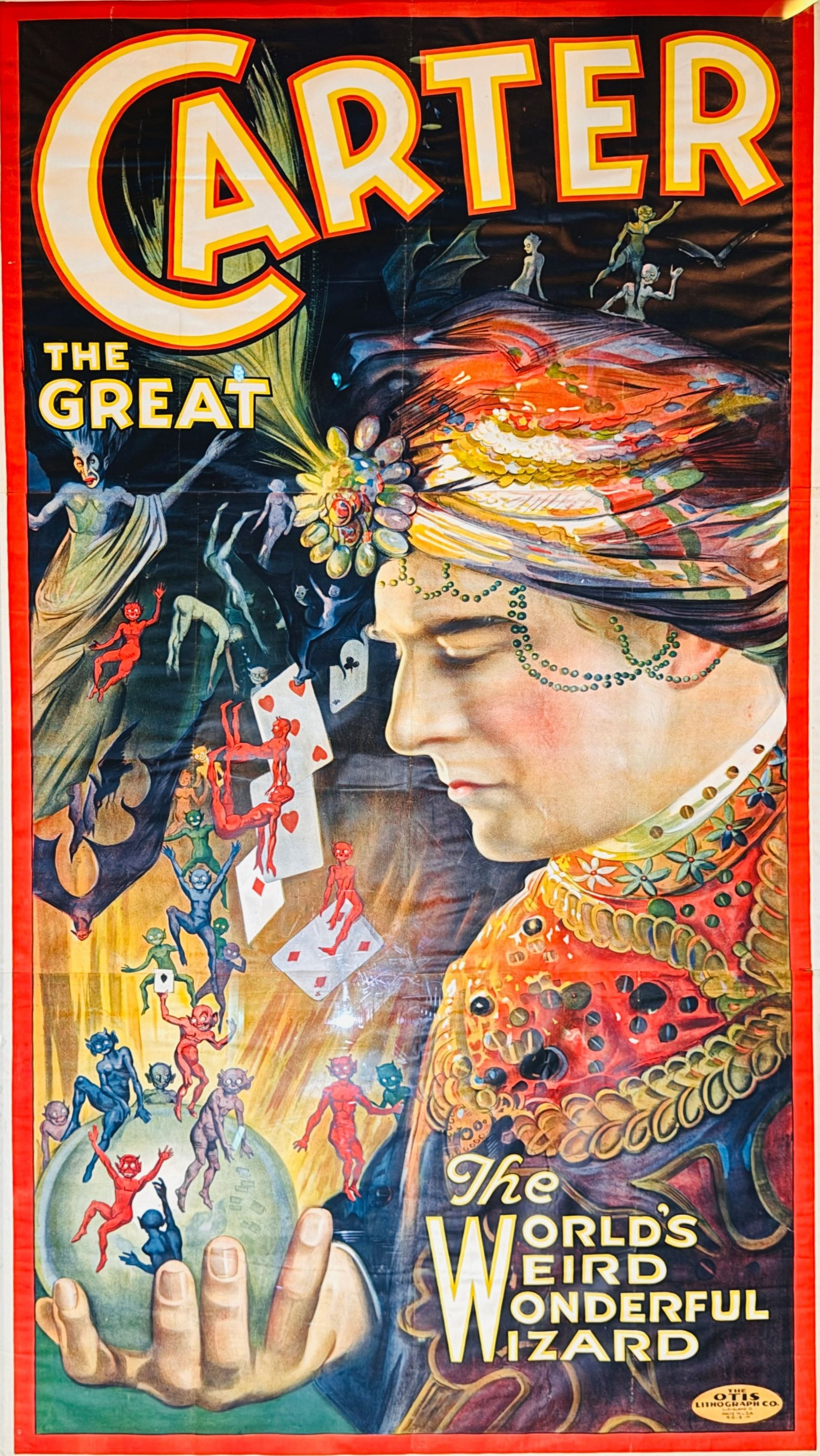

Carter, The World's Weird, Wonderful, Wizard, Otis Litho., 1926. Charles Joseph Carter

B. June 14, 1874 – D. February 13, 1936

Charles Carter was one of the great globe-trotting magicians of the golden age of magic, achieving worldwide fame and a certain international mystique.

Carter had a fascination with magic as a young child. He made his professional debut as “Master Charles, the original boy magician” at the age of ten. He later traveled with a medicine show as “America’s Youngest Prestidigitator.” By age seventeen, he topped a variety bill at a Texas opera house.

In 1894, the twenty-year-old Carter married. He added his new wife, Corinne, to the act. A year later, his son, Lawrence, was born.

Around the beginning of the century, Carter settled in Chicago, where he graduated from law school. To avoid paying an agent 10 percent of his fees, Carter established his own booking office, The National Theatrical Exchange. The principal objective was to keep himself working for the highest possible fees. He also created a trade magazine called “The Chicago Footlights.”

Carter was thirty-one when he embarked on his first world tour. With his fine lithographic poster advertisements and enthusiastic reviews from American critics, people crowded the theaters, with hundreds more turned away.

Despite his successes, touring the world can also be a dangerous endeavor. A plague spread across China. In Fuzhou, a spectator became convulsive and died in his seat during the show. In India, one of his assistants died of scarlet fever. Carter wrote, “Wherever one goes, one shakes hands with smallpox, elbows cholera, or is quarantined against bubonic plague.”

There were other hazards. His company survived a train crash near Bombay. In April 1912, at the end of his second world tour, Carter tried to book passage back to the U.S. on a fancy new ocean liner – however, he was denied passage because many wealthy passengers had already taken up the ship’s storage and there was no room for all of Carter’s luggage and stage gear. That ship was the Titanic. In 1922, he was touring Japan. After a stretch of bad business, the Japanese company seized his props and equipment. Carter’s assistants made a surprise raid on the warehouse, carrying out the crates and baggage. As they were being loaded onto the truck, the warehouse employees rushed out, and a battle ensued. Carter’s crew lost, and the equipment was returned to the warehouse. Carter finally recovered his property five weeks later, and he filed a $22,500 damage suit against the company. It took seven years, but the tenacious Carter won.

Wherever one goes,

one shakes hands with smallpox,

elbows cholera, or is quarantined against bubonic plague.

His first world tour lasted three years and covered a distance that he estimated to be equivalent to three times the circumference of the earth. He took his troupe, including his wife and son, to Australia, New Zealand, India, China, Sri Lanka, Egypt, Italy, the Philippines, and the British Isles.

One of his most popular illusions was a simple chair attached to ropes. His wife Corrine would sit in the chair and be hoisted in the air. Upon his command, she would vanish into thin air, and the chair would crash to the ground. He originally called this illusion “The Magical Divorce” – however, his wife didn’t find that quite as funny as he did. He changed the name of the illusion to “The Phantom Bride.”

In Belgium, he premiered his “Lion’s Bride” illusion. (A copy of the late magician, The Great Lafayette’s Lion Illusion.) It was one of the best investments Carter ever made. It was a bewildering change from a snarling lion to a live magician. It drew five thousand spectators in Lisbon.

This would not be the only illusion Carter would “borrow” from another magician. Theft was an often-used strategy by many of the greatest and not-so-great magicians to complete their shows. Carter also pinched Ching Ling Foo’s production of a huge bowl of water.

After his lion died, Carter attempted to perform a vanishing elephant trick. Models were constructed for several versions, by they did not meet his approval. As he visualized the feat, an elephant would stand on a platform, curtains lowered around it, the platform, and the elephant hoisted up into the air. The curtains were raised so you could see the elephant’s feet; then, the curtain would be dropped. The elephant would disappear. Carter built the apparatus, bought an elephant, and began to rehearse. The elephant would not cooperate, repeatedly lumbering off the platform as it was raised. The illusion became “The Disappearing Flappers,” with four girls vanishing from the platform instead of the elephant.

When the tomb of King Tut was discovered in 1922, Carter quickly developed an Egyptian-themed illusion that capitalized on the worldwide fascination with ancient Egypt following this momentous archaeological find. After John Dillinger’s famous jailbreak in 1934, Carter created an act inspired by the notorious gangster’s escape, tapping into the public’s fascination with crime and daring getaways. By weaving these current events into his performances, Carter ensured that his shows remained exciting and topical, further cementing his reputation as one of the most innovative and adaptable magicians of his time.

Carter made his home in San Francisco, where he purchased a sprawling house in the Seacliff District near the Pacific Ocean. He would perform for small groups in the basement of the house, and there are still occult references in the stained-glass windows. Although sometimes mistakenly referred to as the “Houdini Mansion”, Carter’s house is currently used as a foreign consulate.

The 1933 Chicago World’s Fair attracted millions of patrons. This was during the Depression. Fairgoers flocked to the pavilions filled with free attractions but spent little money on the shows. The “Fort Dearborn Massacre” shut down for restaging. The “101 Ranch Wild west Show” could scarcely pay to feed their livestock. “The Army Show” closed after a twelve-day run. Carter’s lavish “Temple of Mystery” with its exotic Egyptian façade did not attract an audience.

By weaving these current events into his performances,

Carter ensured that his shows remained exciting and topical,

further cementing his reputation as one of the most

innovative and adaptable magicians of his time.

Carter was approaching his sixtieth birthday when he announced his eighth world tour. He journeyed again to Australia and New Zealand, to Singapore, China, and Japan with thirty tons of equipment. His health deteriorated in Hong Kong early in 1935. His son, Larry, took over the presentation of the illusions. He kept traveling to Calcutta in January 1936 and to Bombay in February. In Bombay, he was hospitalized after a severe heart attack.

Carter died the next day.

His friend and competitor, Nicola, summed up his career:

“Carter was not only a great magician but a smart businessman. His show, which he presented in all parts of the world, was a credit to the profession. He mounted it lavishly, billed it like a circus, presented it with dignity and charm.”