The Great FEtaque sanders

By William Pack | Magician, Historian, and Educator, https://libraryprogramming.com/

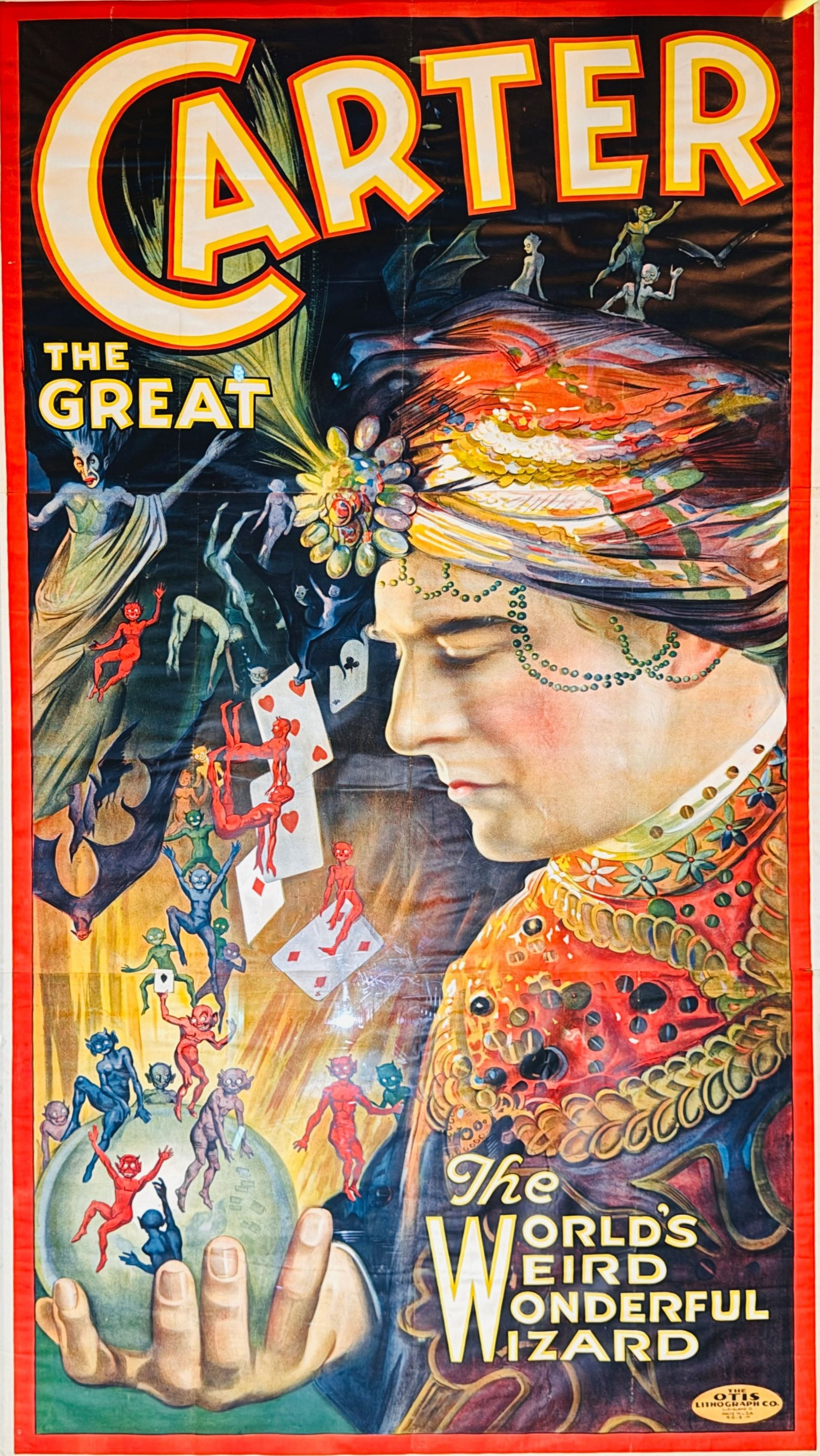

Image courtesy of Potter & Potter https://www.potterauctions.com/

Fetaque Sanders

B. May 12. 1915 – D. June 2, 1992

African American magician Fetaque Sanders (pronounced FEE - take) was born in the front room of his Nashville home at 1601 Heiman St., and as an adult, he lived in that house with his parents every summer when schools were closed, and he wasn’t touring. It would be his home until 1989, when ill health forced him into a nursing home.

He became interested in magic as a child, first developing a love for the theater in Nashville. Seeing a magician, Tricky Sam Tatum, fueled his interest, and soon, he got his first magic set. Fetaque devoured the handful of magic books at his local library. Then, he discovered a private collection on the other side of town. Hidden in the back room of a tailor shop was the library of an exclusive magic club. He was not a member, but the kindly Italian tailor who owned the shop opened the library for him after school.

By the time he was a teenager, Fetaque was doing shows for churches and parties. In 1933, at age 18, he landed a job at the Century of Progress International Exposition, better known as The Chicago World’s Fair. Performing in the Enchanted Island Children’s Theatre was his first major break in show business. When the fair was extended for a second year, he returned.

In 1933, at age 18, he landed a job at

the Century of Progress International Exposition, better known as

The Chicago World’s Fair.

From the World’s Fair, his next step was the circus. He joined in 1935 on the advice of another Black magician, Leon Long, who told Fetaque that the circus would round out his show business education. Fetaque’s father, a dignified community leader, was appalled. The circus manager put Fetaque in a turban and billed him as Feta Sajii. This was the last time Fetaque disguised his race.

After the season, he left to play segregated schools and churches. In the summer, he performed tableside magic at the leading African American nightclubs in Washington, D.C., Chicago, and New York, working alongside Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, and other musical greats.

Fetaque married in 1942, but less than a years later she died of pneumonia.

Shortly after, he received a call to manage a new USO Camp show, and the grieving Fetaque reported for duty. He spent the next three years entertaining more than three million Black soldiers across the country. There were several segregated circuits for African American entertainers. Fetaque was in the first black circuit that performed at U.S. military hospitals.

While with the USO, he met and married Mildred Reed. The birth of his daughter Carolyn was the happiest day of his life.

When World War II ended, Fetaque took to the road, booking segregated schools and colleges in Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Texas, Louisiana, and anywhere else he would be allowed to perform. His reputation and advertising kept him working, and he played an average of two hundred cities yearly.

He spent the next three years

entertaining more than

three million

black soldiers across the country.

A talented artist and craftsman, he built and painted many of his own props. He created his own advertising materials and hand-lettered posters.

But what really made Fetaque a great performer was his personal magnetism. He had a knack for engaging his audience by making them feel they were part of the show. He drove his audiences to near hysteria. He brought down the house with vocal mannerisms, hilarious facial expressions, and an impeccable sense of timing.

The Fetaque Sanders Magic Show appeared at thousands of schools, many of them impoverished, and he brought wonder and delight to children who had never seen a professional stage show. He charged a modest admission. Many of the shows were fundraisers for the schools.

He also endured many hardships due to his race. During World War II, he was arrested by an officer who thought he looked like a spy. He was turned away from restaurants that “didn’t served colored.” During those times, there were places where he couldn’t walk down the street with a White friend because that would have been a problem.

Among magicians, Fetaque was recognized as one of the top showmen and sleight-of-hand artists in the country.

Fetaque toured for twenty-five years. In 1958, he suffered a stroke, which impaired his sight. He continued to perform closer to home into the early 1960s. In retirement, he continued to plan new magic routines, and he tutored a number of magicians, both Black and White.